He de reconocer que no estaba familiarizado con la obra del pintor Juan Carlos Savater (San Sebastián, 1953) a pesar de que lleva más de tres décadas en activo. Lo descubrí gracias a una buena crítica de su exposición en la galería Leandro Navarro, donde se presentan sus cuadros más recientes, pintados entre los años 2010 y 2011.

La exposición está formada, básica y casi exclusivamente, por paisajes de pequeño formato que obligan al espectador a acercarse a ellos para apreciarlos debidamente. Ayudan las recogidas dimensiones de las salas y el silencio de encontrarlas vacías. A poco que observemos, nos damos cuenta de que no se trata de paisajes más o menos bonitos que podemos ver de pasada, como una rápida sucesión de instantáneas fotográficas. Son escenas que desprenden una gran quietud y silencio. Los observo y no estoy seguro de si es la luz lo que me da la sensación de que algo se esconde bajo la apariencia de las cosas, un significado oculto.

|

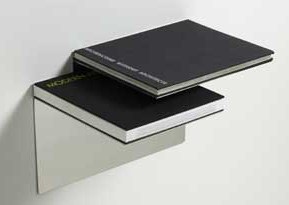

| Guitarristas, 2011 |

Viene a la mente la palabra “místico” antes incluso de ver su constatación en cuadros como Noche verdadera, en el que aparece Cristo seguido de sus discípulos en otro paisaje como los anteriores. De igual modo retrata a un Príncipe Siddharta anciano, ataviado con unas robustas botas de montaña. Pero son las excepciones; no hace falta referente religioso o místico alguno para que las imágenes adquieran ese tinte sobrenatural que trasciende la mera apariencia de los elementos representados. En la línea de los grandes simbolistas, Savater no se detiene en el detalle naturalista o pintoresco. La luz rasante que domina en muchos de los cuadros y los envuelve en un aura entre naranja y dorada monumentaliza las escenas: a medida que avanzamos, se nos hace evidente que allí hay algo más que árboles y montañas. Es fácil acordarse del pensamiento animista que guiaba a los paisajistas románticos del norte de Europa, la idea de que Dios está en todas las cosas. De ahí que no sea necesaria una referencia explícita a la divinidad para que ésta esté presente. Es evidente que nada de esto es ajeno a Savater.

Resulta muy interesante ver cómo, de algún modo, Savater recoge el testigo de la larga tradición simbolista en el arte contemporáneo, desde Caspar David Friedrich a Georgia O’Keeffe, pasando por Van Gogh o Stanley Spencer. En todos ellos, como en Savater, los elementos pintados son sólo intermediarios para revelarnos una verdad oculta. Me atrevería a añadir a la lista de grandes maestros citados a un pintor quizá menos evidente: en el fantástico cuadro de Savater titulado Guitarristas no puedo evitar ver la huella de Edward Hopper y su manera de demostrar que lo más trascendente puede aparecérsenos, incluso, en la intimidad de nuestra propia casa.

Juan Carlos Savater. Obra reciente. Galería Leandro Navarro. Amor de Dios 1, Madrid. Hasta el 31 de octubre.

The revealed truths of Juan Carlos Savater

I must admit that the work of the painter Juan Carlos Savater (San Sebastián, 1953) was not familiar to me although he has been active for over thirty years. I discovered him thanks to a good review of his latest exhibition at Leandro Navarro’s gallery, which hosts his most recent works, painted during 2010 and 2011.

The exhibition is formed, basically, nearly exclusively, by small landscapes that oblige the viewer to get close to them in order to appreciate them as they deserve. It helps to find the small rooms of the gallery empty. It isn’t necessary to observe for very long in order to realize that these aren’t more or less pretty landscapes we can just pass by like a succession of photographs. They are scenes that display great calm and silence. I observe them and I’m not sure if it’s the light that gives me the impression that there’s something hiding under the surface, an unrevealed meaning.

The word “mystical” comes to mind even before contemplating paintings like Noche verdadera, where we see Christ followed by his disciples in a similar landscape to the others. Old Prince Siddharta, wearing a pair of robust hiking boots, is portrayed very much in the same way. But these are exceptions; there is no need for explicit religious or mystical references in the paintings for these to acquire a supernatural tone that transcends the mere appearance of the scenes. Along the lines of the great Symbolist painters, Savater doesn’t pay much attention to naturalistic or picturesque details. The dominating light in many of the paintings, which turns everything a gold-tinged orange, makes the scenes more monumental: as we advance, it becomes more evident that there is something else in these paintings apart from trees and mountains. It’s easy to remember the animistic philosophy that guided the Romantic landscape painters from Northern Europe, the idea that God lives in every human or non human entity. Divinity is present in spite of not being explicitly represented. It is obvious that Savater in not unaware of any of this.

It’s very interesting to see how, in a way, Savater continues the long tradition of Symbolism in modern art, from Caspar David Friedrich to Georgia O’Keeffe, including others such as Van Gogh or Stanley Spencer. In all of them we find, as in Savater, that the painted elements serve only as intermediaries in the revelation of a hidden truth. I would add a maybe less obvious painter to the list of great masters cited: in Savater’s fantastic Guitarristas (Guitarists), I cannot help but see the trace of Edward Hopper and his way of demonstrating that the deepest of meanings can appear even in the intimacy of our very own home.

Juan Carlos Savater. Recent Works. Galería Leandro Navarro. Amor de Dios 1, Madrid. Finishes 31st October.